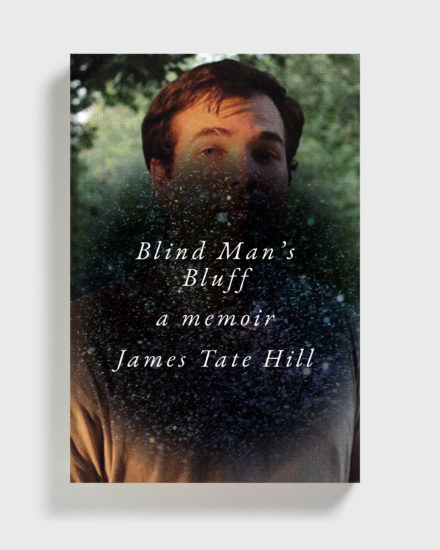

James Tate Hill is the author of the memoir Blind Man’s Bluff, which was published in August 2021 to great acclaim. It’s a memoir about his blindness, and how for a very long time he tried to hide it from his friends, family, the world. You can read more about it—and buy it!—here.

James is also the editor of Monkeybicycle, a fantastic online magazine that publishes short fiction. He’s also one of my favorite people on Twitter—seriously, go check it out. He makes me laugh nearly every time I read one of his tweets.

I’m thrilled that he was able to take some time to talk to me about fear.

What is your greatest fear?

Sharks. Great white sharks. Like many, I saw Jaws at a young age, and the impact was profound. Jaws 2, to be precise, which I maintain is the scariest of the franchise. Growing up in the landlocked state of West Virginia did not mitigate my fear of sharks in the least. In public swimming pools, I didn’t venture into the deep end because the darker shade of blue allowed me to imagine sharks. Never mind that I could see the bottom of the pool.

I didn’t shower until sixth or seventh grade because the chaos of the shower spray could provide cover for, you guessed it, sharks. It was all baths for me until then, and never more than a few inches of water. Also, I couldn’t close my eyes for more than a couple of seconds, which made rinsing the shampoo from my hair more complicated than it should have been.

But I’ve come a long way. I shower without fear, at least most of the time. Swimming pools don’t bother me. And I’ll venture into the ocean all the way to my ankles.

Do you enjoy scaring other people?

I used to, as a child. The appeal has faded substantially as an adult, perhaps upon realizing that I myself do not enjoy being scared. It might also have coincided with my first reading of The Phantom Prince by Elizabeth Kendall, the former fiancée of Ted Bundy. In the book, she recounts how much Ted loved to scare her and her young daughter. Fortunately they both survived to tell about it.

What is your favorite urban legend?

In elementary school, when my family lived in the city, my schoolmates and I referred frequently to someone we called “the killer.” We developed elaborate theories about where he might have been in recent days, concocting narratives around whatever trash we found on the playground. For self-defense, I assembled what I referred to as my “mystery kit,” consisting of old batteries, a mostly empty tube of aloe vera, and a plastic film canister filled with BBs. I stored all of it in the cardboard box of my LEGO firehouse set, bringing it along on sleepovers just in case.

Only now does it occur to me that this generic killer might have been less an urban legend than the neighborhood children’s translation of some actual event. In a city the size of Charleston, WV, it doesn’t seem far-fetched that someone might have committed murder, and that the parents of a second grader might have discussed it in their presence. The opposite, in fact, seems less likely.

What’s something that most people are afraid of that you are not? Why aren’t you?

People often name public speaking as their biggest fear, but it doesn’t bother me. As I write about in Blind Man’s Bluff, I spent a giant portion of my life terrified that strangers would find out about my blindness, a fear that turned routine trips to men’s rooms and classrooms and cafeterias into tense capers straight out of the Cold War. Standing in front of an audience while doing nothing more complicated than talking, by comparison, has never seemed as frightening.

“Growing up in the landlocked state of West Virginia did not mitigate my fear of sharks.”

Is there anything you are terrified of eating? Why?

Shark. Because karma.

I’ll also add anything still living or only recently deceased. Or anything that has ever been consumed during the second round on Fear Factor. Bugs, deer penis, buffalo testicles, earthworms—nope. I highly recommend Dana Goodyear’s Anything That Moves, about the edgier directions food subcultures are heading, for more of those second-round-of-Fear-Factor shudders.

What’s the scariest book you’ve ever read? Is there a particular scene that really haunts you still?

Hands down, the scariest book I’ve ever read is Tim Reiterman’s book about Jonestown, Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People. Many books have been written about Jonestown, and I can recommend several for different reasons, but for me, none will ever surpass Reiterman’s account for its thoroughness and harrowing detail. The author’s connection to the events that unfolded in the days leading to the mass murder of Jonestown’s residents adds another layer to the story. Reiterman was among the reporters who accompanied Congressman Leo Ryan into the jungle to investigate the welfare of residents. If I had to select a scene that has stayed with me most vividly, it might be the tense escape of one Jonestown resident upon realizing everyone was about to die, many unwillingly. The haunting moments, images, and actions go all the way back to Jones’s childhood, and although so much of Jonestown’s story has been misunderstood and misremembered, the parallels to our current politics make Raven scarier still.

What’s worse: the black abyss of space or the black abyss of the bottom of the ocean?

Going to go with the bottom of the ocean. In space, there are no sharks.

What’s the scariest thing you’ve ever written?

I’ve never written horror, other than the short stories I wrote in high school where one character always turned out to be the devil. But that wasn’t a scary devil as much as an I-think-every-story-is-supposed-to-end-with-someone-turning-out-to-be-the-devil devil.

And even if I did write horror, the scary prize would still go to Blind Man’s Bluff. Memoir is the horror franchise with built-in sequels. Even if you survive the gauntlet of past trauma, publication brings the exposure of all your vulnerabilities to total strangers in perpetuity. If that doesn’t give you night sweats, I’m not sure anything will.

What is your earliest childhood memory of fear?

One summer when I was seven or eight, we were visiting my grandparents outside Orlando. It was the height of the 1980s kidnapping of children. I have no reason to believe more children were kidnapped in the mid-1980s, but the ubiquity of missing children on posters, milk cartons, and TV ads made me think my own abduction was imminent. This fear increased in Florida, where the most infamous kidnapping of all, Adam Walsh, had taken place not long before our visit.

Commercials about a missing girl from the Orlando suburb where my grandparents lived played constantly that summer, and the composite sketch of her alleged abductor would haunt me for years. He had curly hair, a narrow face, and a scar on his lower lip. TV ads began with a deep voice saying the word missing, followed by the girl’s name. Every night before bed, I pondered how thick the windows were inside my grandparents’ trailer. Back home, I ventured alone to the toy departments of stores, leaving my parents’ side for the magazines in Kroger and Foodland, but until we returned to West Virginia, fears of being kidnapped kept me tethered to my parents.

Mom and Dad must have sensed how disturbed I was by the missing girl. I recall asking more questions about her disappearance than was probably healthy or normal. Upon returning home, they updated me on her case. They had found the girl. She was okay. Later that year, milk cartons no longer showed pictures of missing children.

Fast-forward to 1997. I was twenty, visiting my grandparents in the same trailer where they had lived a dozen years earlier. I told my Grandma Dot about my fear from that summer for the first time, mentioning the name of that missing girl whose face was everywhere that summer.

“That was such a shame,” said my grandma.

My brow furrowed. “I thought they found her.”

Grandma Dot shook her head. “They found parts of her.”

James Tate Hill is the author of a memoir, Blind Man’s Bluff (W. W. Norton, 2021). His fiction debut, Academy Gothic, won the Nilsen Literary Prize for a First Novel, and the 2019 and 2020 editions of Best American Essays named his works as Notable. He serves as fiction editor for Monkeybicycle and contributing editor for Literary Hub, where he writes a monthly audiobooks column. Born in Charleston, West Virginia, he lives in North Carolina with his wife. Follow him on Twitter @jamestatehill.